By Kenneth Ring, Ph.D.

[Author’s Note. Recently, in writing to a new friend about the problem of empathy, I was reminded of this blog from a few years ago, but also for reasons that will become clear, because her father had loved going to the track for watch horse races. And, finally, this blog makes reference to some of the books I wrote about last week and provides further information about them.]

God blessed them, and God said to them, “Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth and subdue it; and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the air and over every living thing that moves upon the earth.”

I haven’t been able to go to a

zoo for many years. I just can’t stand to see animals penned up or in cages. Even when artificial environments or islands are created for them to give them a little more space to pad around, they are obviously still confined. However delighted children may be to see the animals in their storybooks alive and at close range, from the perspective of the animals themselves who are often bored or dozing in the sun (at least when the sun is shining), they are still inhabiting an open-air prison. Are human prisoners, when they are allowed to go out in their yards for an hour of exercise, any less free than when in their cells? Honestly, I don’t see how any adult visiting a zoo can feel anything but shame and revulsion. Of course, I realize that most adult visitors do not feel any such thing when they wander about gawking at encaged or otherwise imprisoned animals. It’s easy to banish any disquieting thoughts when you see monkeys frolicking about on the trees inside their cages, apparently having a good time. Why shouldn’t you enjoy watching their antics?

But to me, this just shows a blatant if habitual failure of empathy. We view animals from our own privileged perspective as human beings free to move about as we like and, later, to leave them behind as we head for own homes. But what do the animals feel?

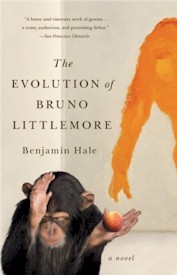

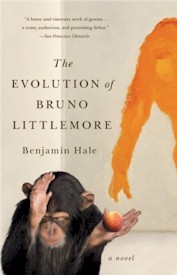

We can turn to literature, to fiction, to get some idea. For example, about ten years ago, by chance, I happened to pick up a book by an author,

Benjamin Hale, of whom I had never heard. The book was called

The Evolution of Bruno Littlemore. It turned out to be the absolute best book I had read in recent years. It tells the story of an encaged chimpanzee named Bruno who is being used for various psychological experiments. At first, he is a brute, a mere beast, covered in his own shit. But one of the psychologist’s assistants takes an interest in Bruno, and believe it or not – remember this is fiction – teaches him to speak. Bruno eventually becomes quite literate. He becomes, if I can put this way, fully human. The assistant, a young woman, even takes him to live with her. (Eventually, he becomes an actor when, after escaping following the woman’s death, he hooks up with a

Falstaffian Shakespearean actor.)

I know this sounds fantastic, and it is of course, but we eventually learn that this book, which is being narrated by Bruno himself who speaks almost as if he is as erudite and articulate as Vladimir Nabokov, is being dictated to a woman named Gwen. At this point, Bruno has been placed in prison. His crime is not having escaped; it is because, in a rage, he has killed the psychologist who, at the beginning of the book, has tormented him with his cruel, self-serving experiments.

But what you learn from this book, which is also riotously funny, is to see the world through Bruno’s eyes, and it is – devastating. What we thoughtlessly do to animals with no regard to their welfare, to treat them as things, not conscious beings like ourselves, for our own ends, now strikes us with the force of a sickening and shocking revelation.

I was so bowled over by this book, I did something afterward I had never done. I wrote the author a fan letter, and he actually responded with a cordial note of his own. Do yourself a favor, friends. If you have a taste for a Nabokovian fantasy, with a more than a touch of Kafka, drop everything and order a copy from Amazon. You will thank me. It may even change your life.

Oddly enough, just recently I came across another book by one of my favorite authors,

T. Coraghessan Boyle (I call him TCBY), called

Talk to Me. It, too, tells the story of a chimp named Sam who becomes literate after he learns to sign. Sam, too, is exploited by an ambitious psychologist who wants to make a name for himself. And as with Bruno, Sam escapes, and after various adventures during which Sam is re-captured and encaged when he again is subjected to the tortured life of a cruelly confined animal (this time by a different psychologist), he is rescued by a woman who has loved him for the start. She is able to abduct him and they come to live together for some time.

After a time, when Sam is still living with the woman, Aimee, who loves him, Aimee is visited by a priest who has heard about Sam and is curious to meet him. He is thunderstruck by what Sam is able communicate to him.

“That’s fascinating,” he said. “Amazing, really. To think that he can express himself, that he can talk – it changes everything, doesn’t it? The church teaches us that animals don’t have souls, or not immortal souls, in any case, but when you consider Sam … allowances have to be made, don’t you think?”

“Sam has a soul, [Aimee] said. “I’m sure of it.”

The idyll will have to end badly, of course. What seems to be a farce will culminate in something like a Shakespearean tragedy.

The second psychologist discovers them and comes to take Sam back, but Sam is having none of it. He viciously attacks the psychologist, maims and blinds him, and then runs off. Again, the motive is revenge! As you can imagine, this does not end well for Sam.

But again, this author has allowed us to see the world through Sam’s eyes. The way humans, especially the men in the book, treat (and mistreat) Sam is revealed as a horror show of heartless exploitation. Aimee’s love, alas, is not enough to save him. Aimee even has to kill him, mercifully with poison, before the authorities arrive to take Sam away, sparing him an even worse fate.

But we don’t have to rely on literature and fantasy to learn the lessons of the need for empathy for the creatures we so routinely and blithely incarcerate but who, unlike Bruno and Sam, must remain mute. They have voices, of course, but they cannot speak their anguish using human language.

Yet there was in fact one in real life who could. Perhaps you are not familiar with a certain inhabitant of the Bronx Zoo who spent some time there more than a century ago.

His name was Ota Benga. He was a pygmy. If you had been alive in 1906 and living in New York, you could have seen him in a cage where he lived with an orangutan. A sign gave you this information about him:

The African pygmy, Ota Benga,

Age, 23 years. Height, 4 feet 11 inches.

Weight 103 pounds. Brought from

Congo Free State, South Central Africa,

By Dr. Samuel P. Verner.

Exhibited each afternoon during September.

The Times covered the exhibit’s opening, noting that Benga and the orangutan “both grin in the same way when pleased.” According to an article about Benga:

The Minneapolis Journal decreed, “He is about as near an approach to the missing link as any human species yet found.” [The zoo’s director, William Temple] Hornaday professed to be puzzled by the outrage, explaining that Benga had “one of the best rooms in the primate house.” But the zoo eventually released Benga to an orphan asylum.

Ten years later, Benga committed suicide, shooting himself in the heart. It turned out he was not 23 when he was encaged; he was only 13. So it was when he was actually 23 that he killed himself.

Encaged animals, not being allowed to carry guns, cannot usually find ways to commit suicide. They must live and suffer the indifferent gazes of passerbys or the delighted shrieks of children.

Of course, our unthinking cruelty to animals doesn’t just apply to those we capture from the wild and then imprison to suffer the immiseration of perpetual confinement. No, hardly. Obviously, there are many kinds of animals we humans confine or restrict in other ways or simply use and exploit for our own pleasure or convenience.

Take horses, for example. Certainly, many people who keep horses love and care for them and develop a personal connection to them. In such cases, there is a kind of reciprocity, even if it isn’t between perceived equals.

On the other hand … In recent years, as I have become more infirm and, in consequence, more sedentary, I have spent a lot of time watching television dramas adapted from famous nineteenth century English novels, often courtesy of the

BBC. In many of these dramas, we see a team of horses chugging away, mile after mile in all sorts of weather, toting along a young girl on her way to becoming a governess for some well-to-do family. I’m sure you have seen many such programs. Our attention, naturally, is on the young girl, wondering what her future will be.

But I often think about the horses, all trussed up and shackled to the carriage, who have no say in the matter. I wonder what they are feeling and what they are thinking. I don’t imagine them to be “dumb brutes,” simply submitting in an unconscious way to whatever demands their master may choose to enforce upon them, seemingly oblivious to the welfare of his horses. For him, they are simply there to do his bidding in blind submission to his will. But for me, I can’t help wondering what the horses themselves feel and if they ever, like quadruped slaves, yearn to break free.

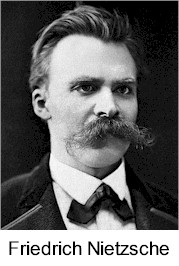

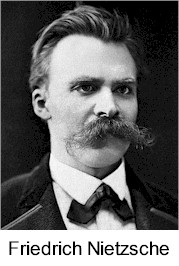

Friedrich Nietzsche, the greatest philosopher of his age, was sensitive to the suffering of harnessed horses. You may know

the famous story about this philosopher who, one morning early in the year 1889, while taking a walk on the streets of Turin, saw a man flogging his horse. Nietzsche, overcome, went to hug the horse, but broke down completely – and went mad. He was already veering toward madness, but it was seeing the beating of a horse that sent him over the edge into the abyss of lunacy from which he never recovered. He spent the last dozen years of his life lost to this one. The psychiatrist,

Irvin Yalom, about whom I wrote in

an earlier blog, based one of his best known novels on this incident, calling it

When Nietzsche Wept.

And then there are race horses. When I was young, I liked to go to race tracks to watch these magnificent animals. But no more. It hurts me to see the jockeys using the whips on their horses, urging them on. Horses clearly love to run and maybe some of them love to win the chase, but have you ever seen one pull up lame? And then we know what is likely to happen to that horse. He or she is done for and will have to be euthanized. Each year, between 2017 and 2019, over a thousand horses died in this way. “The sport of kings” is a blood sport for many horses who have to be sacrificed for our pleasure. We blot these scenes out of our mind and after seeing such a calamity, by the next day we have probably forgotten it. Horse racing continues. See you at the next Kentucky Derby.

I don’t think I have to continue this doleful parade of the way we treat many animals other than our pets. You can think of plenty of examples for yourself. Think of all the cattle we raise, for example, only to be slaughtered. What do they feel when they are being herded into the slaughterhouse? You think they have no idea what fate awaits them? Our relationship to many of the animals we raise for our pleasure can be defined by what I call “the three egregious e’s:” we eat them or exploit them or exterminate them.

On this last point, we human beings have managed to exterminate or cause to go extinct virtually all large terrestrial megafauna. By the end of the century, the elephants and the rhinos will be all but extinct, and probably the lions and tigers, too. If there is still a survivable world, the children growing up then will do so without having direct knowledge of these animals. Maybe there will still be zoos where a token lion will pad around restlessly in a cage, but otherwise children will only know these animals from reading books, just as today, they have to read books about the bygone bison or passenger pigeon. For many animals, aside from our beloved pets, this world has been and continues to be nothing but an abattoir.

Elizabeth Kolbert, a staff writer for

The New Yorker who specializes in environmental issues, wrote a well-received but depressing book a few years back called

The Sixth Extinction. Her wide-ranging research convinced her (and many others, including me) that we are currently witnessing the

sixth major die-off in the evolutionary life of our planet. Most people know only one, when the dinosaurs were wiped out about 65 million years ago at the end of the

Cretaceous period. But we are, Kolbert avers, definitely in the midst of one now. And from what I’ve read, it is affecting our animal kin more than us humans. According to recent reports, in the past several decades,

human population has doubled whereas animal populations on average have declined almost a staggering seventy percent! Our animals are seemingly disappearing from our earth at an alarmingly accelerating rate.

One writer, whom we shall meet in a subsequent blog, has already sounded the tocsin:

How are we to recalibrate our relationship with animals that live in complex societies and have a sense of themselves as individuals? The question becomes more urgent as the future of such species grows increasingly perilous. They are penned in, harassed and hunted, subjected to experiments, eaten, used in medicines … We think that, because we found ourselves on this globe, we have a right to use it for our own sustenance. Animals have the same claim. They, too, didn’t choose to be where they are.

It may of course be too late, just as it may be too late to arrest the onset of devastating climate change, but certainly one contributing factor to our present desperate plight has been the persistence of a seemingly ineradicable anthropocentrism that privileges human life above all others. But human beings are not on the top of some kind of imagined evolutionary ladder. Evolution more resembles a bush with many branches rather than a ladder with humans at its pinnacle.

Unfortunately, however, human beings are incontestably the alpha predator on the planet. We have no serious terrestrial predators (it’s only the viruses that can do us in). Some animals, such as bears and tigers, may maul us to death if they get close, but animals don’t have guns, much less missiles and bombs. We can and have killed animals at will and with impunity, often just for sport, and have done an excellent job of destroying their habitats as well. All this is well known. The question is, at this late hour, what can be done?

It occurs to me that in the nineteenth century, we virtually abolished slavery. In the twentieth century, the woman’s suffrage movement finally triumphed. In our own day, we have found our way to begin to protect the members of the LGBTQ community. All of these achievements have been possible because of the extension of legal rights to these populations. And because we need urgently to revision our relationship to our animal brethren, perhaps it’s time to consider in effect a bill of rights for animals.

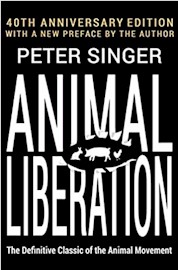

Animal welfare efforts, while laudable, have failed. Australian philosopher,

Peter Singer, whose 1975 groundbreaking book,

Animal Liberation, seemed to promise a new day for animals, recently expressed disappointment that his movement, as important has it has been, did not achieve more. We need something more, something more radical, before the door of opportunity closes on our fingers.

Recently, a number of thinkers and animal rights activists have begun to wage a last ditch effort to achieve a meaningful way to establish a moral and legal framework for animals. My next two blogs will explore this new approach for animal justice and we will begin by returning to the Bronx Zoo.

Here is a preview of who we will be meeting there:

According to the civil-law code of the state of New York, a writ of habeas corpus may be obtained by any “person” who has been illegally detained. In Bronx County, most such claims arrive on behalf of prisoners on Rikers Island. Habeas petitions are not often heard in court, which was only one reason that the case before New York Supreme Court Justice Alison Y. Tuitt—Nonhuman Rights Project v. James Breheny, et al.— was extraordinary. The subject of the petition was Happy, an Asian elephant in the Bronx Zoo. American law treats all animals as “things”—the same category as rocks or roller skates. However, if the Justice granted the habeas petition to move Happy from the zoo to a sanctuary, in the eyes of the law she would be a person. She would have rights.

Because of space limitations, I will be forced to give only a very brief description of Avni’s experience. It will include more about what led to his becoming comatose and what he experienced during the forty-four hours of his ordeal. For this purpose, I will draw on and slightly edit the abstract that Nahm et al provide:

Because of space limitations, I will be forced to give only a very brief description of Avni’s experience. It will include more about what led to his becoming comatose and what he experienced during the forty-four hours of his ordeal. For this purpose, I will draw on and slightly edit the abstract that Nahm et al provide: