For those of you who may not be familiar with the life and work of Swedenborg and his significance as a religious prophet and reformer of the teachings of Christianity, I should perhaps take a moment to say something about this remarkable man. Until his fifties, he had distinguished himself in many branches of science including paleontology, physics, anatomy and physiology, several of which he had pioneered. He was famous and celebrated for these achievements and many others, but in April, 1744, when he was in his mid-fifties, he underwent a spiritual crisis during which he was taken into the spiritual world and came to know many things about what happens to us after death. After that he wrote many books about what he was shown through his visionary revelations having to do with heaven and hell, about the how the Bible should really be understood and about divine love and wisdom. His best known work was called Heaven and its Wonders, and Hell, and is still read. Today, Swedenborg is honored as a religious mystic and revelator of towering importance for the understanding of Christianity and a seer.

As a result of these heavenly visitations, Swedenborg also became very psychic, and there are any number of documented instances during which he knew things that he could not have known by normal means. One of the most famous concerned a fire that broke out in Stockholm where Swedenborg’s home was. At the time he was in Gothenberg, about 250 miles away. I first read about this incident in a book I no longer have, so I will just avail myself of the account given in Wikipedia:

When the fire broke out Swedenborg was at a dinner with friends in Gothenburg, about 400 km from Stockholm. He became agitated and told the party at six o'clock that there was a fire in Stockholm, that it had consumed his neighbor's home and was threatening his own. Two hours later, he exclaimed with relief that the fire had stopped three doors from his home.

Days later, two separate reports about the fire finally reached Swedenborg. Both of these reports confirmed every statement to the precise hour that Swedenborg first expressed the information.One of my favorite stories about Swedenborg, which I first read about in one of the books in my library I once had, concerned the prospective visit that the famous 18th century English theologian, John Wesley hoped to pay Swedenborg. Wesley had come to hear about Swedenborg’s teachings and was eager to meet him. At that time, Wesley was on one of his extensive speaking tours, but sometime in 1771 he wrote Swedenborg to propose that they meet after his return on March 29, 1772. As I no longer have the exact quote of Swedenborg’s answer, I will have to rely on my memory. As I recall, Swedenborg replied with something like these words, “Dear esteemed sir, I very much regret I will not be able to meet you on that day for I am to die on the date.” And he did.

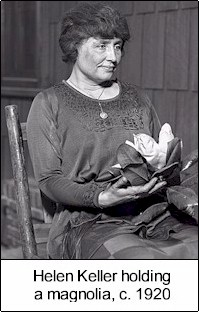

None of this, of course, was important to Helen; she probably didn’t even know about these stories. What mattered to her was what Swedenborg taught about life after death. For Helen, her discovery of the Swedish seer was a revelation, and she was enthralled by his teachings. His view of Christianity and the afterlife was, as she put it, “the light in my darkness, the voice in my silence.” And what did Swedenborg proclaim? Death, he said, is simply a transition into a new and wonderful world, and from what he taught, Helen understood that when she entered that world she would not only be able to see and hear but would enjoy the kind of conjugal love that her earthly life had denied her.

As she wrote to John Hitz:

Swedenborgianism is more satisfying to me than the creeds about which I have read… I feel weary of groping, always groping along the darkened path that seems endless… But when I remember the truths you have brought within my reach, I am strong again and full of joy. I am no longer deaf and blind for with my spirit I see the glory of the all-perfect that lies beyond the physical light and hear the triumphant song of love which transcends the tumult of this world.

Helen would become a devoted follower of Swedenborg’s teachings for the rest of her life. She studied his religious philosophy by immersing herself in his writings, read the Bible every morning, usually the Psalms, and every Sunday celebrated her religion privately in her home. Just as socialism had become her secular truth, so when she had found Swedenborg, she discovered her life-sustaining spiritual truth and would later write about its importance to her in her 1927 book, My Religion.All this is really prelude to where I want to take this essay, and for that, I need to make some personal comments about my own connection to Swedenborg.

I first learned about Swedenborg when I read Raymond Moody’s book, Life after Life, in 1975, the book that introduced the world to the term, “near-death experience.” Toward the end of that little book, in a section called “parallels,” Moody spends a few pages on Swedenborg to show something astonishing: In virtually all important respects Swedenborg’s writings describe exactly what near-experiencers report about the experience of dying. How did he know this? Simple: His “angels” had guided him through death’s door so he could know what it was like to die as well as what would happen afterward.

That naturally intrigued me, too, so in the early years of my own research into NDEs, I began to read some books about Swedenborg as well as relevant sections of his masterpiece, Heaven and its Wonders and Hell. (A personal aside: Some years ago, when I had to downsize my own professional library, I gave away about 400 of my books, including those by and about Swedenborg.) I could see that Moody was right, so I began teaching a little bit about Swedenborg in my NDE course at the University of Connecticut and in some of my public lectures.

Meanwhile, modern-day Swedenborgians, having also read or heard about Moody’s book, latched onto NDE studies, too, as they felt this work also provided independent verification of Swedenborg’s teachings. (After Swedenborg’s death, various churches were established to promulgate his teachings.) And soon enough, they latched onto me as well once they learned I was partial to Swedenborg. At the time, I was heading up The International Association for Near-Death Studies (IANDS), and one venerable and wealthy Swedenborgian gentleman eventually became a good friend of mine and joined the board of directors at IANDS. After that, I often visited him and his community in Bryn Athyn, Pennsylvania, which is the home of one of the branches of the Swedenborg church, The General Church of the New Jerusalem. And although I am very far from an authority on Swedenborg – hardly! – but because of my familiarity with his writings pertaining to life after death, I was sometimes asked to write introductions to books about Swedenborg and also contributed an article on Swedenborg and NDEs to a beautifully produced volume published in 1988 by the Swedenborg Foundation in New York commemorating the tri-centennial anniversary of his birth.

Now to relate all this to Helen Keller, I must draw on some material of mine in my book, Waiting to Die, in which I wrote about my own difficulties with my vision and how, like Helen, I took comfort, not just from what Swedenborg had taught about life after death, but what I had learned from my many years of studying and researching NDEs.After describing the various ocular maladies that I have had to endure ever since I was born, I continued in a whimsical mode:

Are you beginning to get an idea of my visual world? Unfortunately, my vision has deteriorated quite a bit since I started writing these essays. Nowadays, I don’t see as much as I infer the existence of what we were once pleased to call the external world. I mean, if the street where I walk was there yesterday, I assume it must still be there today. But my vision is getting to be a joke. For example, the other day, as I was completing my warm-down after my stint on my stationary bike, I happened to pass by my next door neighbor, who was walking her dog. I did recognize that a dog was coming toward me, but I failed to recognize my neighbor. Just call me Mr. Magoo of Marin.

But then I turned to what I had learned from my studies of NDEs:

Well, you can see – no pun intended since that verb is largely conjectural for me now – that I have my reasons for hoping that I won’t have to wait too much longer to have better vision. No, there is no operation that can help me.

The only thing that can – is death! And now I will tell you why I have cause to think that one day, perhaps before too long, I will have perfect vision.

One of things that first struck me so forcibly when I was starting out on my life as an NDE researcher was how often my respondents would comment on how well they could see (and hear) during their NDEs. Here are some of those remarks from my first book on NDEs, Life at Death.

I could see very clearly, yeh, yeh. I recognized it [her body] as being me.

My ears were very sensitive at that point… Vision also.

I heard everything clearly and distinctly.

Seems like everything was clear. My hearing was clear… I felt like I could hear a pin drop. My sight – everything was clear.

It was as if my whole body had eyes and ears.

Years later, one of my students, who had had an NDE, and who had previously lost most of the hearing in one of his ears, told me he could hear perfectly during his NDE.

And it’s a similar story for people who are poorly sighted, but not during their NDE. Consider the following case of a 48-year-old woman who reported this experience following post-surgical complications. All of a sudden:

Bang. I left. The next thing I was aware of was floating on the ceiling. And seeing down there, with his hat on his head [she is referring to her anesthesiologist]… it was so vivid. I’m very near-sighted, too, by the way, which was another one of the startling things that happened when I left my body. I see at fifteen feet what most people see at 400… They were hooking me up to a machine behind my head. And my first thought was, “Jesus, I can see! I can’t believe it, I can see!” I could read the numbers on the machine behind my head and I was just so thrilled. And I thought, “They gave me back my glasses.”

Things were enormously clear and bright… From where I was looking, I could look down on this enormous fluorescent light… and it was so dirty on top of the light. [Could you see the top of the light fixture, then? I asked.] I was floating above the light fixture. [Could you see the top of the light fixture?] Yes [sounding a little impatient with my question], and it was filthy. And I remember thinking, “Got to tell the nurses about that.”

Even more astonishing than the fact that those with defective vision seem to see perfectly during their NDE is the finding from my own research on the blind (he said modestly) that clearly shows that even persons who are congenitally blind -- people who obviously have never seen in their lives – can and do see during their NDEs. As one of these persons whom I interviewed for my book, Mindsight, where I present about thirty of these cases, and who had had two NDEs, said: “Those experiences were the only time I could ever relate to seeing, and to what light was, because I experienced it. I was able to see.”This testimony comes from a woman named Vicki who was 43 when I first met and interviewed her in Seattle. In the course of her interview she told me that during her (second) NDE, when she was 22, which took place in a hospital, she found herself up by the ceiling and could clearly see her body below (she recognized it from seeing her hair and also her wedding ring). She continued to ascend and eventually came to be above the hospital, where she saw streets, buildings and the lights of the city. She also told me that she saw different intensities of brightness and wondered if that was what people meant when they referred to colors.

Vicki was only one such case of the congenitally blind who reported some kind of vision during their NDE; as I’ve mentioned, there were others. How such eyeless vision, which I called mindsight, can occur is something I speculate about in my book, but the fact that it occurs is incontestable, however inexplicable it appears.

What does all this research have to tell us about the kind of body we may find ourselves in after death? Of course, no one can say with certainty, but the implication is that it will be one in which all of the senses we have in our earthly body are somehow able to function with perfect clarity. And if that’s so, it stands to reason that whatever infirmities or physical limitations we have here will be absent there.

Think of it this way. When we dream, we are usually not aware of any bodily limitations. Indeed, we may not even be aware of having a “dream body.” I know that in my own dreams, I am aware of myself, but not my body. Now, don’t misunderstand: An NDE is in no way like a dream; it is far more real. From the standpoint of an NDE, it is more real than what we call life, and certainly more real than even the most vivid dream. Nevertheless, our dreams are perhaps the best intimation of the wonders that await us after we die. And in that state, the one that we can anticipate when we die, all bodily malfunctions appear to be transcended.

When I contemplate such possibilities, I know it makes it a lot easier for me to deal with the signs of my own creeping decrepitude and my increasingly poor vision. I know that they are only the temporary impediments of my aging body.

In any case, you can now understand that I am not just waiting to die. I’m waiting to see. Perfectly.

***************************************

Helen Keller died gently in her sleep in 1968, a few weeks before her 88th birthday. That was before the modern study of NDEs began with the publication of Moody’s book in 1975. So Helen would never had been able to learn about this work, but if she had, she would, I’m sure, have found it credible and confirmatory of what she had long believed. And deeply comforting.When she was an old woman, she was visited by the actress, Lilli Palmer, who later recounted her conversation with Helen:

Her face, although an old lady’s face, had something of a school girl’s innocence… It was a saintly face.

“There’s so much I’d like to see,” she said, “so much to learn. And death is just around the corner. Not that that worries me. On the contrary.”

“Do you believe in life after death?” I asked.

“Most certainly,” she said emphatically. “It is no more than passing from one room into another.”

Suddenly, Helen spoke again. Slowly and very distinctly she said, “But there’s a difference for me, you know. Because in that other -- room – I shall be able to see.”

I have every reason – and now you know why – to believe that when Helen passed into the next world, she would indeed finally have been given sight, the wonders to behold.